The Challenge of Reaching and Teaching in Southern Mexico

In their Introduction to Global Missions, Zane Pratt, David Sills, and Jeff Walters define a missionary as “someone who intentionally crosses boundaries for the purpose of communicating the gospel.”[i] Those boundaries come in many forms—culture, geography, language, religion, socioeconomics, etc.—but fundamental to being a missionary is crossing these kinds of boundaries, or barriers, to carry the gospel to people living on the other side.

As a missionary in Mexico, I’m sometimes asked if Mexico really needs more missionaries. Doesn’t Mexico already have a lot of missionaries? Why should we send more?

Behind these questions usually lies the assumption that Mexico is generally monocultural, and that once the gospel is sown, churches are planted, and leaders are trained in a certain area the gospel will naturally spread outward across relatively “barrier free” terrain. But this simply isn’t the case.

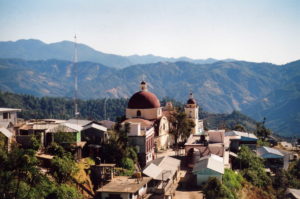

My family and I serve missionaries in Mexico’s southern state of Oaxaca. Oaxaca is a land of barriers. These barriers are deep, well-established, and, in most cases, centuries in the making. As Mexico’s most indigenous state, Oaxaca is home to more than one million indigenous language speakers. The majority of these people live in thousands of isolated mountain villages with fewer than 500 inhabitants, making Oaxaca one of the most culturally diverse places in the world. To understand Oaxaca’s diversity and the challenges it brings to the work of missions, it’s helpful to understand the barriers that create that diversity.

Geographical barriers

The most obvious “barrier” is Oaxaca’s geography. As a mountainous coastal state, elevations range from

zero to over 12,000 feet above sea level, with an average altitude of about 5,000 feet. Oaxaca’s extensive mountain ranges create a highly fragmented topography. Because of this extreme topography, closely neighboring villages are often separated from each other by imposing mountains and plummeting valleys, resulting in almost complete isolation. Oaxaca’s geographical conditions create obvious challenges for missionaries. My particular ministry is leadership training. Our task is to find effective ways to provide Biblical training for the many hundreds of indigenous churches sprinkled throughout these mountains. There’s a lot of work to be done.

Linguistic Barriers

But beyond geographical fragmentation is Oaxaca’s extreme linguistic and ethnic diversity. Although Spanish is the official language of Mexico, there are 16 indigenous language families (or “macrolanguages”) in Oaxaca, most of which consist of multiple languages. For example, within Mixtec, one of the largest of these language families, there are over 50 different languages.[ii] Some of these are similar to one another to varying degrees, but most of them are mutually unintelligible, warranting their own Bible translations. Similarly, the Zapotec language family has nearly 60 languages, most of which, again, are mutually unintelligible and warrant their own individual Bible translation.[iii] The result is over 160 distinct languages in the state of Oaxaca alone [iv] (Click here for an ethnolinguistic map of Oaxaca).

Serving in Oaxaca has afforded me the opportunity to get to know many of the translators whose job it is to translate the Bible into Mexico’s approximately 300 indigenous languages. Their task is a daunting one. Because these languages trace their roots to ancient, Pre-Columbian tribal languages, they have no affinity to the North American and European languages that we’re familiar with, making them extremely “foreign” to us. For example, the vowel-abundant, tonal Mixtec spoken in one village where we’ve worked sounds more like a Southeast Asian language than Spanish. (Example: “Máá rí cúu staā jeē cótecu rō nɨɨ́ cáni sáha.” Translation: “I am the bread of life,” Jn. 6:48.)

Needless to say, the linguistic diversity of Oaxaca creates challenges for missionaries, and not just Bible translators. As a leadership trainer, I’m faced with the challenge of teaching men whose mother tongue, like my own, is something other than Spanish, and who often struggle to understand and communicate in their second language. I spent last weekend in a Zapotec village working with the soon-to-be appointed leaders of an indigenous church. Although the church uses the traditional Spanish translation of the Bible, their services are conducted almost entirely in Zapotec. On a superficial level, most people seem to understand Spanish well enough, but in personal conversations it quickly becomes clear that much is lost in translation, especially when it involves people over, say, 30 years old. These factors make training much more challenging.

Cultural Barriers

Added to the linguistic barriers is the distinctiveness of the cultures found in Oaxaca. Because these tribal groups have lived in relative isolation for centuries, they have maintained many of their ancient customs and ancestral traditions. These customs and traditions often vary from village to villages, with neighboring villages often having distinctive rituals, belief systems, superstitions and even clothing. Because of the isolation and cultural distinctiveness of individual villages and groups, a person’s social identity—his sense of belonging—is not usually based on language, geography, or ethnicity, but on his own community—his own village. This means that while researchers may categorize a group of villages as one “people group”, the reality is that the villages themselves may share little or no sense of affinity with each other.

The divisions created by these cultural barriers have been exacerbated by the famously volatile political

atmosphere of indigenous Oaxaca. Centuries of oppression and abuse from foreign invaders, rival tribal groups, and the Mexican government have resulted in people who are often reclusive and highly suspicious of outsiders. Land wars and other intra-village disputes are a constant source of conflict and violence, and create sometimes bewildering scenarios for outsiders trying to navigate these complex cultural waters.

Thankfully, the gospel is the most powerful barrier-penetrating force in the universe. Our mutual identity in Christ goes far to break down the cultural barriers that would normally separate us from the church leaders we seek to train. Nevertheless, the barriers are real and always present. They require that we approach our ministry as learners, always seeking to better know and understand the people that we’re called to serve.

Pastoral training is not one-size-fits-all. Each culture has its own unique worldview. Churches in these cultures face their own unique set of challenges and issues. To cross these cultural and worldview barriers we must enter the lives of these people. Effective pastoral training requires far more than giving formal classes. It requires relational life-on-life mentoring. This is true in any culture, but it’s especially true in contexts where trainers and trainees come from radically different cultural backgrounds.

Religious and Spiritual Barriers

But the biggest barriers we face is, undoubtedly, the spiritual one. Mexican indigenous religion is highly syncretistic, blending elements of folk Catholicism and ancient tribal animism. A couple of years ago a missionary friend of mine showed me a video he recorded of his Mixtec village’s shaman making an animal sacrifice—complete with an altar, the sprinkling of blood, and ritual dances. The sacrifice is made each year at the beginning of the rainy season to invoke the favor of “El Señor de La Lluvia,” the “Lord of the Rain”—the rain god. Ironically, the name they’ve given to their god is “St. Mark”—a striking example of the syncretism that has taken place between animism and Catholicism. The resultant spiritual darkness is evident.

And again, training church leaders in these contexts poses unique challenges. Applying God’s word to our own cultural and religious contexts is not always easy. Effectively teaching others to apply Scripture to their own radically different cultural contexts requires a great deal of wisdom from above.

Yet God Is at Work

The fragmentation and isolation of Oaxaca’s indigenous population creates significant boundaries for the spread of the gospel and unique challenges for the task of training indigenous church leaders. But in spite of these boundaries and challenges, the gospel has had amazing success in penetrating deep into these mountains. God is at work, and the gospel is unmatched in its ability to cross the most impassible of barriers.

[i] Pratt, Zane; Sills, M. David; Walters, Jeff K. (2014-07-01). Introduction to Global Missions (Kindle Locations 170-174). B&H Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

[ii] See https://www.ethnologue.com/country/MX/languages.

[iii] See http://www.mexico.sil.org/es/lengua_cultura/zapoteca.

[iv] See https://www.ethnologue.com/language/zap for a list of Mexico’s indigenous languages. For another list and map of Mexico’s ethnolinguistic groups see http://en.etnopedia.org/wiki/index.php/Mexico.

Want More Content Like This?

We will deliver Reaching & Teaching articles and podcast episodes automatically to your inbox. It's a great way to stay on top of the latest news and resources for international missions and pastoral training.